Technological glitches, downed laptop, desktop mail snafus, telephone recording device used during interviews dies minutes before an important interview… if I didn’t know better, I’d say gremlins had invaded my office. Add in your basic case of overload mixed with mild panic and you have a picture of my unproductive day. I’ll be back tomorrow.

Author: Devra Hall Levy

Patriotic Jazzmen

I am continually amazed by the number of legendary jazz musicians who have served our country, in uniform, carrying instruments in lieu of weapons. Music has the power to break barriers, be they barriers of geography, ideology, religion, or other discriminations.

Prior to 1920 (when more than one thousand warrant officer positions were authorized and their jobs expanded to include clerical, administrative, and band leading activities), military musicians were either enlisted men or commissioned officers — and none were black. Expanding the role warrant officers allowed the military to recruit superior musicians who were not otherwise qualified for officer status.

Racial integration has historically been a piece-meal operation, in or out of the military. It was through music that President Roosevelt found one way to elevate the status of black men in the Navy. Before World War II, blacks in the Navy were mess men or stewards, boot blacks or stokers. Through the Great Lakes Experience (1942-1945), the US Navy recruited 5,000 black musicians and trained them as bandsmen at the Great Lakes Naval Training Center in Illinois. This act added dimension to the great history of the Navy Band Great Lakes, which was founded in 1917 by Lieutenant Commander John Philip Sousa.

My husband, John Levy, a jazz bassist living in Chicago, might have been one of the Great Lakes recruits, but he was not. In December of 1941, he was on the road again with the Cabin Boys, this time headed for Warren, Ohio. He was en route one Sunday, listening to the car radio, when he heard that the Japanese had bombed Pearl Harbor. “Everybody in those days was feeling patriotic, and I was no exception,†he remembers. “There were role models in my family. My Uncle Johnny, Mama’s oldest brother, had fought in the Spanish-American War. Then years later, Uncle Sherman was one of the 300,000 blacks who fought in WWI.†John wanted to join the Army Signal Corps, so when he got back to Chicago, he took lessons and scored high, 98.2 on the test. A few months later he was called for an appointment, but when he got there they refused to accept him, despite his high score. “We don’t take niggers in the Signal Corps,†they told him.

That experience left a scar and killed his desire to enlist, but it did not hamper his feelings of patriotism, nor did it stop him from supporting the war effort or entertaining the troops. Several years ago, while writing his biography, I discovered a letter from the United States Treasury Department thanking him for his “efforts in furthering the sale of War Bonds and Stamps,†probably a thank you for his participation in the War Bond Jam Session in the Mayfair Room of Chicago’s Blackstone Hotel. The letter was dated April 1944, and was addressed to him in care of the Garrick Stagebar where he had a steady gig playing bass with the Stuff Smith Trio. One day the trio went to the Navy base to entertain. “The Great Lakes Navy Band with Willie Smith, Ernie Royal and Clark Terry also played that day,†John reminisces. “That band had great musicians, guys we didn’t get to hear often around town.â€

In a 1978 interview posted on the Jazz Institute of Chicago’s web site, trumpeter Clark Terry told Charles Walton, “When we finished our boot camp we received our ratings, which was displayed by having a lyre sown on our sleeve. To see a Black man in a United States Navy with a lyre on his sleeve instead of a C, which meant cook, was quite an oddity.â€

Many of those musicians went on to have stellar musical careers after their military service. A few years ago, The Great Lakes Naval Training Center celebrated the 60th anniversary of “The Great Lakes Experience of World War II,” and paid tribute to the Navy’s first black musicians. Clark Terry was there, along with composer/bandleader Gerald Wilson. Both men have earned more honors and awards than either can count. My husband and I saw both of them together at a January 2004 gathering of National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters. Gerald Wilson received a Jazz Master award in 1990 and Clark Terry got his in 1991.

My father’s musical experience vis a vis racial bias has been from the opposite end – he was “the white guy” in the celebrated Chico Hamilton Quintet back in 1955. And with the Sonny Rollins quintet he was “the white guy” featured on the legendary album titled The Bridge. People have asked him about his experiences and he refuses to see it as black and white. He views music as a way of bonding people together and crossing barriers, be they barriers of geography, ideology, religion, or other discriminations. He is also an NEA Jazz Master (2004), and in his acceptance speech he said, “The women and men who have received this award in the past have spread peace and love throughout the world, something that governments might emulate. I am pleased to be one of the peacemakers.â€

If music is the language of humanity, then every musician, in or out of uniform, will be a peacemaker, musical instruments will be standard issue, and wars will be resolved diplomatically, in concert.

F Sharp

Where is Django’s guitar? The Epiphone that Django Reinhart played when touring the US with Duke Ellington was given to Cleveland-born guitarist Fred Sharp by Django’s son, Babik, in 1985. (The story of Django’s Epiphone, a 1946 Zephyr #3442, can be read here.)

The two guitarsts, Fred and Babik, were brought together in 1967 by Charles Delaunay, noted French critic, Django biographer, and founder of Jazz Hot magazine. (Jazz Hot, started in 1935, may be the oldest jazz magazine in the world.) Fred has written about Babik here and about Delauney here.

I met Charles Delauney when I was 16 years old. I was in France with a teen travel group called The Experiment in International Living, and after spending a few weeks living with a farming family in the Jura Mountains where I learned how to milk cows and bale hay, the Americans and one similarly aged family member from each of the host families took a bus trip all the way down to Nice. Riding down the Promenade des Anglais in the bus I saw huge posters everywhere heralding Le Grande Parade du Jazz, the festival produce by George Wein. To make a long story a little shorter (you’ll have to wait for my memoir for all the details), I ran into Ed Thigpen who arranged for me to see that night’s show, and it was there, listening to Ella Fitzgerald, that I met Delauney. When he learned that I would be in Paris about a week later, he said to call, which I did, and that led to a delightful afternoon at Versailles followed by une crème glacée at a lovely little cafe.

Google led me to an article about Delauney titled Magnificent Obsession: The Discographers, by Jerry Atkins. It seems that the first discographies almost simultaneously sprang into being in 1936 — in Melody Maker (a British weekly), Dalauney’s Hot Discographie (in Paris), and Hugues Pannassié’s Hot Jazz (in the US) — but Atkins writes, “Charles Delaunay is probably the father of discographical format as we know it today. ”

But geting back to Fred, who has played and recorded with Pee Wee Russell, Mugsy Spanier, Miff Mole, Red Norvo, and Jack Teagarden, among others. It was Fred who, in 1946, sent a young songwriter named Joe Bari to pitch his song to Frankie Laine. Bari sang the song for Laine, who said, “What do you need me for? You sing great!” There’s more to this story written up by Joe Mosbrook, but Bari later became famous as Tony Bennett.

Fred also happened to be Jim Hall’s first guitar teacher. I haven’t had the pleasure of meeting Fred in person (he lives in Florida now), but we do exchange occassional emails. About a month ago he wrote:

When I first moved to Sarasota in 1990, I started teaching guitar ( a big mistake) at Gottuso’s Music Shop. I had a young man, about 15 or 16 come to me and asked if he could study with me. I told him, “I only teach Jazz”, to which he replied, “Oh…I already took that!”

Music On The Brain

I have long been curious about how and/or why music causes various visceral reactions. I wonder, for example, why is it that modulating keys gives one a lift. In search of some answers, I am reading Music, The Brain, and Ecstasy: How Music Captures Our Imagination by Robert Jourdain. (This is not a new book; first published in 1997, and the paperback reissued by Quill in 2002.) Jourdain’s explainations evolve from sounds… to tone…to melody…to harmony…to rhythm…to composition…to performance…to listening…to understanding…to ecstasy, and his ten chapters are so named. I haven’t reached ecstasy yet — I’m only as far as rhythm — but here are a few interesting tidbits (the italics are mine):

“Laboratory studies show that untrained adults discern contour almost as well as profesional musicians. So contour is central to our experience of melody.” Harmony, or “melody in flight” is a required dimension to hearing melody, as is rhythm. “Some musicologists have described harmony as music’s third dimension, its depth dimension (with breadth of time and the height of pitch space as the first two dimensions).”

“Harmony needs dissonance just like a good story needs suspense…Only after lengthy expeditions in other harmonic realms, realms that orbit lesser tonal centers, is the listener granted release from his agony. Inferior composers make quick, perfunctory returns to tonal centers, or travel so far from them that the listener hardly recognizes them when finally brought home. The trick is to find just the right balance between reinforcing tonal centers and violating them.”

“With experience, our brains acquire a vocabulary of these common progressions…Halfway through hearing them, we anticipate their endings. They are musical cliches. But a talented composer can take advantage of this fact by encouraging the listener to anticipate a standard ending yet writing something different. When the chord anticipated and the chord actually heard are aptly chosen, the contrast can be blissully excruciating.”

What He Said

“I have said that poetry is the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings: it takes its origin from emotion reflected in tranquility.” — William Wordsworth

I’ve Got Mail: Jazz In The Woods

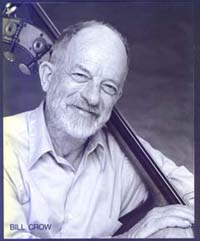

The Bill Crow photo I posted previously was a tad dated, so Bill sent me this one taken by Judy Kirtley (wife of pianist Bill Mays) a little over a year ago. He wrote of the first photo:

The Bill Crow photo I posted previously was a tad dated, so Bill sent me this one taken by Judy Kirtley (wife of pianist Bill Mays) a little over a year ago. He wrote of the first photo:

That’s an old picture of me, back when I had more hair. It was taken at Struggles in Edgewater, NJ, on the last gig that Al and Zoot played together before Zoot passed. (That’s Zoot’s shoulder sharing the photo with me.)

Bill also told me that he is going on vacation, and taking his tuba with him:

It’s nice to practice on the deck of our cabin in the wood…the tuba sounds lovely ringing out across the treetops and distant hills. No complaints from the neighbors or the deer so far.

That’s a scene I can clearly envision, not because I have such a great imagination, but because I have seen a similar sight. Here is the first paragraph of the liner notes I wrote for Jim Hall’s 1997 CD, Textures.

The screened-in porch of the Hall country retreat is in the middle of the woods. The birds chirp and the chipmunks splash through the fallen leaves getting ready for winter. The cacophony of the city is far away and here we sit, my father and I, talking about Textures, his latest recording. From my perspective this project reveals a startling and wonderful new persona.

Coincidentally, this CD includes three pieces written for a brass ensemble. I know that the tuba has a long history in jazz, but outside of marching bands, it’s not heard all that often these days. My favorite tune from this recording is Circus Dance, a lumbering waltz for two trumpets, trombone, tuba, guitar and drums. [I’ve posted a pdf of the liner notes here]

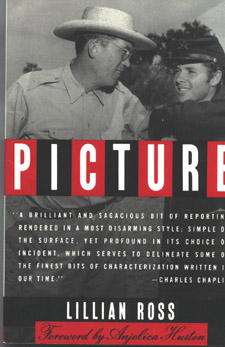

“Picture” by Lillian Ross

One of my goals as a narrative nonfiction writer is to make my readers to feel as if they are there, seeing the events about which I am writing. In order for that to happen, I have to evoke the readers’ interest and convey to them a sense of my reliability, letting them know that either I was there observing (and now they can watch through my eyes) or at least that I did thorough research. Lillian Ross is a master in this genre and I often try to analyze her work in search of techniques that I might employ. Her ability to capture dialogue without aid of a tape recorder is truly amazing (and something I may never be able to do as skillfully as she), but there are a few techniques I can emulate.

One of my goals as a narrative nonfiction writer is to make my readers to feel as if they are there, seeing the events about which I am writing. In order for that to happen, I have to evoke the readers’ interest and convey to them a sense of my reliability, letting them know that either I was there observing (and now they can watch through my eyes) or at least that I did thorough research. Lillian Ross is a master in this genre and I often try to analyze her work in search of techniques that I might employ. Her ability to capture dialogue without aid of a tape recorder is truly amazing (and something I may never be able to do as skillfully as she), but there are a few techniques I can emulate.

Get out of the way. Ross uses the words “I,†“me,†and “we†only a few dozen times throughout the entire book. Her presence is thoroughly established in the opening chapter, where we readers are most acutely aware of her presence and participation in the scenes with John Huston and Arthur Fellows at the hotel suite and restaurant outing. After that, Ross uses only the occasional I/me/we to re-orient and reassure the reader that the knowledge is first-hand.

Tell the story, without bias or judgment, as if talking to a friend. At the end of the very first paragraph, Ross clearly defines herself as an observer who wishes to learn about “the American motion-picture industry†by following the process of the making of this one particular movie. This implies the role of both student and reporter, roles that are inherently unbiased and nonjudgmental (at least they were at that time). What she doesn’t state directly, and indeed it is not necessary to state, is that what she really is interested in is not so much the industry, but the people in the industry. She never verbalizes her/our questions, but by laying out the answers, the questions are implied throughout the narrative. It is as if she is a friend telling me about this movie project, and I can hear myself saying, “You’re kidding! Then what happened?â€

Juxtapose and illuminate seeming contradictions to give a fuller picture. Her choice of what to include/exclude belies her fairness and compassion. There are no moral interpretations or judgments, just the facts and enough narrative to place actions and words within a full context. Ross juxtaposes Huston’s physicality with his sensitivity, perception, and intelligence. He’s 6-foot-2 with “long arms and long hands, long legs and long feet,†he drinks hard, plays hard, lights his matches with his thumbnail, and “the bridge of his nose is bashed in.†Yet he adopted an orphaned boy and knows that 12-year-olds are more intelligent than they are given credit for, he loves the quality of the dusk light, and he sees Audie as a “little, gentle-eyes creature.â€

Descriptions become sharper and more memorable with the use of contrasts and comparisons. Ross uses contrast as a descriptive tool throughout – for example, contrast between a person’s inner and outer characteristics, and between one person and another. Similarly, she uses comparison, but it is never overt. By putting two characters/descriptions within proximity she ‘invites’ the reader to see the deeper contrast. For example, when Spiegel arrives during filming at the ranch, we see Huston, “his face blackened by smoke and his shirt and trousers stained with sweat and grime†being greeted by Spiegel who was “immaculate in brown suede shoes, orange and green Argyle socks, tan gabardine slacks…â€

When many characters are involved, introduce each on his turf and include as much action as possible. Picture begins with a series of scenes, each of which introduces the main characters in appropriate locations. First John Huston in New York, then producer Gottfried Reinhardt in his office full of status details, then MGM’s production VP Dore Schary at Chasen’s Restaurant, and finally Louis B. Mayer in his huge cream-colored office. Keep up momentum and variety throughout the book. The next scenes take us around the studio lot which keeps us in motion as we continue to meet other players and discover the commissary, projection room, wardrobe, casting, and other dept offices, all the while getting back story and details about the movie process. The longest sustained scenes throughout the rest of the book tend to be the shooting scenes, but the pace is varied by the many other shorter scenes, brief conversation snippets, and reprinting of primary source materials such as memos and letters.

A little detail goes a long way. The moviemaking process can be tedious; full of retakes and long waits. To recreate the process fully yet not bore the readers, Ross compresses time without losing content. For example, she covers a few hours of rehearsal time with one single paragraph, but this conciseness is balanced with details of magnitude (“ten thousand five hundred lunchboxes would be served at a cost to Metro of $15,750—one of the smaller items in the picture’s budgetâ€) and details of minutia (prop man asks Huston to choose which one of the three small, squealing pigs is to be stolen from the farm girl).

And last but not least, the story must be about more than the specifics – good stories address broader issues and themes. On one level this is the specific story of the making of one movie, “The Red Badge of Courage†based on the Stephen Crane novel about the Civil War, and of the individuals involved. On a second level it is about the world of movie making – we learn a bit about music scoring, recording the music to film, dubbing sound, filming, cutting/editing, and even the preview process. On a third, much broader level, the more abstract message is that the more things change, the more they stay the same…and life goes on.

Note: Da Capo Press published a 50th anniversary paperback edition of Ross’ “Picture†in June 2002.

Reality?

Sunday’s New York Times piece, The Rise of the Winner-Take-All Documentary by A. O. Scott is about film, but it applies just as well to print, and to me, that’s a problem. Here’s an excerpt from the first graf and a half:

…For a screenwriter in search of third-act drama, the climactic sports showdown is a surefire winner. And also, of course, a cliché. Even in movies based on real-life sports figures and events – “Cinderella Man,” “Friday Night Lights” and “Seabiscuit” are some recent examples – the big game can feel a bit rigged. And yet, even if we know what’s coming – or, for that matter, what really happened – we can’t help succumbing to the rush of suspense and emotion that the spectacle of high-stakes, winner-take-all competition brings.

Why should documentaries be any different? Perhaps the biggest challenge in nonfiction filmmaking, as in some forms of journalism, is the shaping of cluttered, contingent experience into a coherent story. The world supplies an abundance of interesting personalities, important subjects and relevant issues, but narratives of a momentum and clarity sufficient to sustain 90 minutes’ (or $10) worth of attention are harder to come by…

Scott mentions journalism, and I draw a parallel between documentaries and narrative nonfiction. In fact, the movies “Seabiscuit” and “Friday Night Lights” were based on narrative nonfiction books of the same titles.* My problem is that I like to write about ordinary people going about their ordinary lives, and more often than not, there is nothing momentous at stake. As a nonfiction writer seeking to be paid and published, I must now look for narratives of a momentum and clarity sufficient to sustain a long feature, if not a book, because interesting personalities, important subjects and relevant issues are, in and of themselves, no longer enough.

There may be those who argue that those elements never were sufficient, but the climate has changed. I am deeply disturbed by the mass appeal of reality tv where everything is a contest, even finding a spouse and landing a job. The humongous prizes add components of upward mobility for the winner, devestation or at least serious disappointment for the losers, transformation, and maybe, just maybe, some self-revelations along the way. All the narrative elements are there, the stories are true (albeit manipulated), but I don’t want to buy into the life as a winner-take-all sport.

*Note: The screenplay for the movie “Cinderella Man” appears to be original, and not based on any of the books with that title; the hardcover by Jeremy Schaap and an upcoming paperback by Michael DeLisa (an historical consultant for the movie) were based on Braddock’s life, and the paperback by Marc Cerasini was based on the screenplay.

Describing Real People – Addendum

In today’s New York Times, in an article by Holland Cotter titled “The Innovative Odd Couple of Cézanne and Pissarro,” I came across two sentences that I must share in light of my last night posting:

Cézanne was a furious misfit with the face of a hobbit, the mind of a scholar and the mouth of a stevedore. Pissarro … was a yippie who happened to look like a monk.

Here’s a Cézanne self-portrait and Pissarro as seen by Pissarro. What do you think?

Describing Real People

“The people will bring the places alive.” So says Bill Zinsser, author of the classic On Writing Well, Mitchell & Ruff: An American Profile in Jazz, Easy to Remember: The Great American Songwriters and Their Songs, and American Places, to name just a few. He said that while teaching a nonfiction writing course he calls “People & Places.” It’s been more than a few years since I sat in Zinsser’s classroom, but I remember him, and the room, quite well.

The wood strip coat racks that line two of the walls have jutting protuberances on which to hang one’s garments — some straight out like nails with super large heads, others at upward angles like single handle water faucets. They are all bare due to the temperate weather of a pleasant Fall evening. The walls appear pale gray, either because they are, or because the florescent lights overhead cast a dingy shadow on aging off-white paint. There is the faint hum of a fan; the air is dry, odorless. Zinsser is spry, trim, with glasses sporting square-ish lenses. His brow is furrowed, perhaps from editing too many student pages filled with passive and not so passive clutter. He is wearing a green striped jacket, white shirt, dark grayish-blue slacks with a brown belt, dark socks, and tennis shoes. Putting down his canvas bag with blue trim, he loosens his blue polka-dot tie to get comfortable. By way of introduction, he tells us that he’s “a fourth-generation New Yorker with roots deep in the cement.” His mother was a “mad clipper” of newspaper articles, so perhaps it should not be surprising that he always wanted to be a newspaperman at the Herald Tribune, and thought that the Herald was put out just for him. “I set out to get an education and have an interesting life,†he tells us.

It was in Zinsser’s class that I first began to really appreciate short but revealing people sketches. Here are a few descriptions, read or re-read in more recent years, that I like a lot. (If the first one sounds familiar it’s because I quoted the first sentence earlier this month.)

Mrs. Reed in Walt Harrington’s At the Heart of It: Ordinary People, Extraordinary Lives:

At ten in the morning, heading out the front door, Mrs. Reed is a vision of vitality in slow motion. She wears a simple blue-flowered dress and a white spots jacket, opaque stockings, white flats (she wore short heels the other day and vanity cost her a strained muscle that hurt so bad she could barely walk until she doctored herself with Ben-Gay), and a pretty turquoise beret, beneath which she tucks her short dark-gray hair.

Four of the workers in Gay Talese’s The Bridge

Cicero Mike, who once drove a Capone whiskey truck during Prohibition and recently fell to his death of a bridge near Chicago…

Indian Al Deal, who kept three women happy out West and came to the bridge each morning in a fancy silk shirt…

Riphorn Red, who used to paste twenty-dollar bills along the sides of his suitcase and who went berserk one night in a cemetery…

the Nutley Kid, who smoked long Italian cigars and chewed snuff and use toilet water and, at lunch, would drink milk and beer – without taking out the snuff…

Mrs. Clare in Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood:

Her celebrity derives not from her present occupation but a previous one—dance-hall hostess, an incarnation not indicated by her appearance. She is a gaunt, trouser-wearing, woolen-shirted, cowboy-booted, ginger-colored, gingerly-tempered woman of unrevealed age (“That’s for me to know, and you to guessâ€) but promptly revealed opinions, most of which are announced in a voice of rooster-crow altitude and penetration.