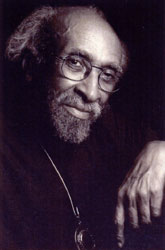

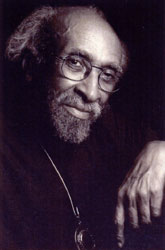

Luther Henderson is not a household name, not even a B-list celebrity in the eyes of the general public. Finding a publisher for his biography has been a lengthy and difficult process, but I am pleased to say that I am in negotiations right now and hope to announce a signing very soon. Meanwhile, people are asking me “Luther who?”

Luther Henderson was a composer, arranger, conductor, musical director, orchestrator, and pianist. He was a proud black man who graduated from the Julliard School of Music in 1942, and in 1956, married a white woman, his second wife. He was Duke Ellington’s “classical arm,†orchestrating music for Beggar’s Holiday, Three Black Kings, and other symphonic works. Duke spoke highly of Luther, but seldom gave him the credit he was due. Luther was Lena Horne’s pianist and musical director. During his sixty-year career in music, he worked his magic on some of Broadway’s greatest musical hits, including Flower Drum Song, Funny Girl, No No Nanette, Purlie, Ain’t Misbehavin’, and Jelly’s Last Jam, starring such performers as Barbra Streisand, Laine Kazan, Robert Guillaume, Savion Glover, Andre Deshields, Tonya Pinkins, and Gregory Hines. His music was heard on television programs such as The Ed Sullivan Show, The Bell Telephone Hour, and specials for the pop stars of the day including Dean Martin, Carol Burnett, Andy Williams, Victor Borge, and Polly Bergen.

Luther Henderson was a composer, arranger, conductor, musical director, orchestrator, and pianist. He was a proud black man who graduated from the Julliard School of Music in 1942, and in 1956, married a white woman, his second wife. He was Duke Ellington’s “classical arm,†orchestrating music for Beggar’s Holiday, Three Black Kings, and other symphonic works. Duke spoke highly of Luther, but seldom gave him the credit he was due. Luther was Lena Horne’s pianist and musical director. During his sixty-year career in music, he worked his magic on some of Broadway’s greatest musical hits, including Flower Drum Song, Funny Girl, No No Nanette, Purlie, Ain’t Misbehavin’, and Jelly’s Last Jam, starring such performers as Barbra Streisand, Laine Kazan, Robert Guillaume, Savion Glover, Andre Deshields, Tonya Pinkins, and Gregory Hines. His music was heard on television programs such as The Ed Sullivan Show, The Bell Telephone Hour, and specials for the pop stars of the day including Dean Martin, Carol Burnett, Andy Williams, Victor Borge, and Polly Bergen.

Despite the success of these shows, on both stage and television, his contributions were never properly valued. What reason, or combination of reasons, led to this oversight? Certainly there were those who usurped credit, whether due to ego, carelessness, or resentment of Luther’s training and talent. Was he caught between two worlds – the elite classical world embodied in his Julliard training, and the world of jazz, his own heritage? Both worlds viewed him with suspicion; neither took him seriously. Was it due to the racial biases of the times? Or was it just the inevitable fate of a background man?

Those in the business understood his talent, but it is hard to communicate to an audience just what Luther really did. We value a composer above an arranger or orchestrator, thinking that one is more original and creative than the other. When music is described as ‘incidental,’ the word used for background music as opposed to featured songs in a show, we assume it is, well, incidental, not very important. Even ‘background’ conveys lack of importance. Most of Luther’s major projects were based on songs written by others, but the difference between a song in its original form and Luther’s orchestration based on that song is vast. Luther’s interpretation is every bit as creative as the original song. He tried to explain it in an interview for American Theatre magazine in 1997:

Sometimes I call it ‘translating’ the music, but it’s more like transporting the music. It’s going through me, and I’m enjoying it going through me, and I’m adding to it what happens when it passes through me. I don’t try to imitate Duke Ellington. I can’t copy Jelly Roll Morton. I can’t be Fats Waller. But I can express what Fats Waller, Jelly Roll Morton, and Duke Ellington mean to me. I can be the conduit.

Luther lived his life largely in the shadows, yet he never saw it that way. He was an affable man who appeared to view his experiences through proverbial rose-colored glasses, and for the most part, that is truly how he saw things. He lived as though he had plenty of money, but he was poorly compensated and he never liked to ask for proper recompense. He believed his work was important, but he said he enjoyed it so much, that it didn’t seem right to be paid. He thought everyone loved him – and most people did, but some didn’t. Growing up black in America, embracing both jazz and classical music – one, an American art form that has yet to be fully appreciated, and the other, a field not truly open to blacks at that time – was not a path to fame and fortune. But with a love of music, a prodigious talent, and an optimistic outlook, that is the life he chose. It was a life that required extreme dedication and concentration, sometimes to the detriment of family relations and his role as husband and father.

On Sunday, July 31st, pianist Hank Jones will celebrate his 87th birthday, just shy of one year for each key on the piano. Hank was born in Vicksburg, MS on July, 31, 1918, and NPR’s Jazz Profiles, hosted by Nancy Wilson, is celebrating. Check the NPR web site to see when the program airs near you and check out the audio clips of pianists Sir Roland Hanna and Billy Taylor talking about Jones’ personal approach to the piano, and Hank’s own reminiscences of listening to Fats Waller on the radio, watching Art Tatum practice, working on The Ed Sullivan Show, and constantly striving for excellence.

On Sunday, July 31st, pianist Hank Jones will celebrate his 87th birthday, just shy of one year for each key on the piano. Hank was born in Vicksburg, MS on July, 31, 1918, and NPR’s Jazz Profiles, hosted by Nancy Wilson, is celebrating. Check the NPR web site to see when the program airs near you and check out the audio clips of pianists Sir Roland Hanna and Billy Taylor talking about Jones’ personal approach to the piano, and Hank’s own reminiscences of listening to Fats Waller on the radio, watching Art Tatum practice, working on The Ed Sullivan Show, and constantly striving for excellence. July 31st is also guitarist Kenny Burrell’s birthday — born in Detroit, MI in 1931, he will be 74. A prolific recording artist and composer, Kenny is also the Director of the Jazz Studies Program at UCLA Department of Ethnomusicology His UCLA faculty bio is here and the bio on the Verve Music Group web site is here.

July 31st is also guitarist Kenny Burrell’s birthday — born in Detroit, MI in 1931, he will be 74. A prolific recording artist and composer, Kenny is also the Director of the Jazz Studies Program at UCLA Department of Ethnomusicology His UCLA faculty bio is here and the bio on the Verve Music Group web site is here.

Luther Henderson was a composer, arranger, conductor, musical director, orchestrator, and pianist. He was a proud black man who graduated from the Julliard School of Music in 1942, and in 1956, married a white woman, his second wife. He was Duke Ellington’s “classical arm,†orchestrating music for Beggar’s Holiday, Three Black Kings, and other symphonic works. Duke spoke highly of Luther, but seldom gave him the credit he was due. Luther was Lena Horne’s pianist and musical director. During his sixty-year career in music, he worked his magic on some of Broadway’s greatest musical hits, including Flower Drum Song, Funny Girl, No No Nanette, Purlie, Ain’t Misbehavin’, and Jelly’s Last Jam, starring such performers as Barbra Streisand, Laine Kazan, Robert Guillaume, Savion Glover, Andre Deshields, Tonya Pinkins, and Gregory Hines. His music was heard on television programs such as The Ed Sullivan Show, The Bell Telephone Hour, and specials for the pop stars of the day including Dean Martin, Carol Burnett, Andy Williams, Victor Borge, and Polly Bergen.

Luther Henderson was a composer, arranger, conductor, musical director, orchestrator, and pianist. He was a proud black man who graduated from the Julliard School of Music in 1942, and in 1956, married a white woman, his second wife. He was Duke Ellington’s “classical arm,†orchestrating music for Beggar’s Holiday, Three Black Kings, and other symphonic works. Duke spoke highly of Luther, but seldom gave him the credit he was due. Luther was Lena Horne’s pianist and musical director. During his sixty-year career in music, he worked his magic on some of Broadway’s greatest musical hits, including Flower Drum Song, Funny Girl, No No Nanette, Purlie, Ain’t Misbehavin’, and Jelly’s Last Jam, starring such performers as Barbra Streisand, Laine Kazan, Robert Guillaume, Savion Glover, Andre Deshields, Tonya Pinkins, and Gregory Hines. His music was heard on television programs such as The Ed Sullivan Show, The Bell Telephone Hour, and specials for the pop stars of the day including Dean Martin, Carol Burnett, Andy Williams, Victor Borge, and Polly Bergen.